Right now, one of the most well-known Black athletes in Slippery Rock says people are more scared of getting kicked out of school for plagiarism than for racism.

Jermaine Wynn Jr. was incensed. His friends in Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. (AKA) were dealing with the frustration that came with a senseless, racially motivated Zoom bombing. Something needed to be done.

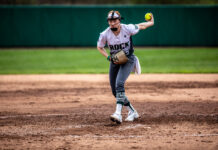

Wynn, a senior wideout who’d ranked fifth in the nation in receiving yards last football season, reached out to his team’s head coach, Shawn Lutz, and told him how he felt about what had happened. Lutz invited Jermaine to his office and, before he knew it, he was speaking on a video call with Slippery Rock University President William Behre.

“There’s not a lot of presidents at universities that will promptly respond to a text from a coach saying, ‘I have a player here that’s upset,’” Wynn says. “I poured my heart out to President Behre and I understood the tough position he’s in dealing with these situations.”

The talk broadened Wynn’s perspective on how Behre deals with such instances. A week ago, Wynn says, he would have been much more frustrated and fired up about what had happened.

“[I’ve realized] what he’s doing to try to diversify the people who work here and the steps he’s taking to try to fix this type of stuff and make Black students feel more comfortable around this community,” Wynn says. “It was definitely settling and I appreciated it a lot.”

The receiver brings up a point that Behre introduced in conversation.

“[Behre] thinks these racial tensions will continue to flare up because that’s who’s losing power in the world,” Wynn says. “People who believe in these certain things, they’re slowly but surely becoming unpopular. It’s becoming unpopular to be a racist. It’s becoming unpopular to do things like what happened at our university.”

Wynn reiterates another idea, from what he described as a recent heated debate with teammate Dalton Holt.

“He said, ‘We’ve got to make these people who want to do things like that—you know, bomb Zoom meetings and deface Black History posters—we’ve got to make them feel like they’re the minority,” Wynn said. “We’ve got to make them feel like it’s not cool to be racist.”

This August, it will have been five years since former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat for the national anthem for the first time. Even in sparking an ongoing dispute, the protest served its purpose of bringing awareness to topics such as police brutality and systemic racism.

Wynn has had conversations with people who disagreed with and were irritated by the act. Though, with all that has transpired since then, Wynn says, those same peoples’ perceptions have changed.

“I think [activism in sports] has opened a lot of people’s eyes,” Coach Lutz says. “I think it’s been nothing but a positive thing.”

Wynn speaks about the impact Kaepernick has had, in particular.

“I do think Kaepernick taking that knee [has] definitely influenced a lot of what’s going on today in terms of us speaking out,” Wynn said. “Even with all of the athletes and all of the influential people speaking out on this, I think we still have a long way to go to completely fix this issue of race.”

This summer, tensions reached a fever pitch and protests were organized nationwide.

Lutz’ stance, he stresses, is that he is white and, because of that knowing he couldn’t comprehend such issues, his team needs to know he cares. As a group over Zoom meetings, he listened as Black players and staff detailed their experiences of racism, profiling, and inequality.

“It’s hard for me to say, ‘Hey, I understand what you’re going through,’” Lutz says. “To me, the Black players are the only ones that know that, that deal with racism.”

The team’s coaches, said Wynn, went above and beyond in bringing the team together during the turmoil that followed George Floyd’s murder this past summer. Aware and understanding of what was going on, the players fully embraced it.

About what happened with Floyd’s murder, Lutz says, “There’s just got to be accountability for people’s actions. We talk in our program about accountability and that needs to be in society, as well.”

“I’m pretty sure there’s a lot of teams out there who just kind of brushed that type of stuff off to the side,” Wynn says. “We had players that were just able to voice how they felt and voice their experiences with things like that. I think it really opened up a different perspective for our white players, they come from much different places than a lot of our Black players.”

Wynn is aware that you can’t change everyone who’s in the locker room’s views. Preventing a divide because of this only takes buying into the team’s culture, he says.

“I think [Black players] just want to have a voice,” Lutz says. “To have a voice [with which] they can communicate their concerns and how they feel […] There’s guys hurting on our football team and there’s guys hurting probably everywhere. To me, there’s been a lot of good changes in sports.”

The personal encounters that Wynn shares are those he’s had with police officers.

“My first ever time being pulled over by a police officer, his reasoning was because he told me that my hoodie on my head looked suspicious,” Wynn says. “As a first-time driver and a first time experiencing something like that, it really messed me up in a way.”

The officer ended up writing Wynn a ticket for rolling through a stop sign, but Jermaine says that the first thing he said was that he began following him because of how he was wearing the hood of his sweatshirt. To this day, Wynn doesn’t wear a hoodie while driving, and he feels that he has to fix his posture in front of the wheel so not to give an officer a reason to stop him.

Being pulled over again and treated with respect, Jermaine gained two perspectives of the same sort of situations. Wynn feels like, due to the number of cases of police brutality posted online, that, at a certain point, it can become commonplace to or desensitize those who are watching.

“When I actually find myself in a situation, and me being a Black man, I’m always scared to death,” Wynn says. “It’s important for Black men to know, let your pride go when you get pulled over. Even if you don’t think you did anything wrong, prove it through court. Don’t try to prove it through that officer. Who knows if that officer is not having a good day?”

It’s not easy for some to share their experiences, Wynn says, balling his right fist and putting his pointer finger and thumb parallel to each other.

“What I shared about getting pulled over, that’s only probably about this much of the harshness some of my teammates said,” Wynn says.

While Jermaine is a football player at the school, with the ability to easily get in touch with President Behre, he realizes that thousands of other Black students at the school don’t have the same privilege of communication.

“I think the school needs to voice [its] support for [its] Black students a little more,” Wynn says. “Not just in February on Black History Month. It’s not a secret that […] you drive through town and see Confederate flags and stuff. We all know, in a way, what that symbolizes to some people.”

Wynn does understand the difficulties that Behre runs into, but also believes students should face more consequences for such heinous acts.

In addition to his conversation with Behre, Wynn also joined him in listening in on a recent Black Action Society meeting. Over the course of the gathering, a number of Black students expressed that they would not recommend SRU to other minorities looking for a college to attend.

“I don’t want that from the place I’ll call my alma mater,” Wynn said. “I want to be able to refer this university to anyone. And it was kind of sad hearing a large portion of the Black students say [that], […] so whatever I can do to try to help change that narrative, I’ll be full-go for my next semester-and-a-half.”

Wynn adores the raucous cheers heard throughout campus on fall Saturdays and, in his personal experience, he’s been treated well by the outside community.

“Once we’re off that field, we’re not really identified as Black or white,” Wynn says. “We’re pretty much identified as Rock football players and I think that’s actually a problem, also. I don’t want to just be identified as a football player because I’m much more than that. And that’s why it’s always been important for me to have a footprint in the community.”

Lutz agrees with this value.

“Love to me […], it’s more caring about them as an individual than a football player,” Lutz says. “So whatever they feel they need to do as an individual, as long as they’re doing it the right way, they’re being respectful, and they’re trying to make a change, we on our staff and in our program fully support that.”

Wynn goes on to explain that the interactions in the town are minimal, though, and he doesn’t necessarily feel comfortable walking into community business.

“Usually I just want to get in there and get out,” Wynn says. “Because, usually I have eyes on me for some reason. People are staring at me […] Other than being identified as just a Rock football player, I can’t really say that I have [heavy] community support as a Black person.”

Players can find a safe haven in the locker room, especially with Lutz’ backing.

“We’re a family,” Lutz says. “We always talk and communicate and have those uncomfortable conversations […] When there’s something that’s going on that needs to be discussed—a world topic, a problem with inequality and racism—we don’t mind having those [talks].”